Imagine you’re standing in a lush garden on a bright summer day. The sun is shining, birds are chirping, and a gentle breeze rustles through the colorful flowers. You want to capture this beautiful moment forever. That’s where a camera comes in – a magical device that can freeze time and preserve memories. But how does this marvel of technology actually work? Let’s embark on a journey to unravel the mysteries of the camera, following the path of light as it transforms into the images we cherish.

Chapter 1: The Camera Obscura – Where It All Began

Our story starts centuries ago, with a simple yet fascinating phenomenon called the camera obscura. Picture yourself inside a dark room on a sunny day. There’s a tiny hole in one of the walls, and suddenly, you notice something extraordinary on the opposite wall – an upside-down image of the outside world!

This is the basic principle behind all cameras, and it’s surprisingly simple. Light travels in straight lines, and when it passes through a small opening, it projects an inverted image of the scene outside. Early artists used this technique to aid in their paintings, tracing the projected images to create lifelike representations of the world.

Chapter 2: Capturing Light – The Role of the Lens

Now, let’s fast forward to modern cameras. While they still use the same basic principle as the camera obscura, they’ve got a few tricks up their sleeve to make things even better. The most important of these is the lens.

Think of a lens as a sophisticated version of that tiny hole in the camera obscura. It’s a curved piece of glass (or plastic) that bends light in a very specific way. When light passes through a lens, it gets focused onto a single point. This allows our cameras to capture much brighter and sharper images than a simple pinhole would.

To understand how a lens works, imagine you’re using a magnifying glass to focus sunlight onto a piece of paper. By adjusting the distance between the magnifying glass and the paper, you can make the spot of light smaller and more intense. Camera lenses work in a similar way, focusing light onto the camera’s sensor (which we’ll talk about later).

In this diagram, you can see how light rays (red and blue lines) from different angles are bent by the convex lens to converge at a single point, called the focal point. This is how a camera lens focuses light to form a sharp image.

Also check: Introduction to Cloud Computing

Chapter 3: The Magic of Aperture – Controlling Light and Depth

Now that we understand how lenses focus light, let’s talk about a crucial feature of camera lenses: the aperture. The aperture is like the pupil of your eye – it can open wide to let in more light or narrow to let in less.

Imagine you’re in a dark room, and someone suddenly turns on a bright light. Your pupils would contract to let in less light, protecting your eyes. Similarly, when it’s dark, your pupils dilate to let in more light so you can see better. The aperture in a camera lens works the same way.

But the aperture does more than just control the amount of light entering the camera. It also affects something called the “depth of field.” This is photography jargon for how much of your image is in focus.

Let’s use an example to understand this better. Picture yourself taking a photo of a friend standing in front of a beautiful mountain landscape:

- With a wide aperture (small f-number like f/2.8), you can focus on your friend, making them sharp while the mountains in the background appear blurry. This is great for portraits where you want to emphasize the subject.

- With a narrow aperture (large f-number like f/16), both your friend and the mountains can be in focus. This is perfect for landscape photos where you want everything to be sharp.

This diagram illustrates how aperture affects depth of field. On the left, a wide aperture (f/2.8) results in a shallow depth of field, where only the subject (green rectangle) is in sharp focus. On the right, a narrow aperture (f/16) produces a deeper depth of field, keeping more of the scene in focus.

Chapter 4: Shutter Speed – Freezing Time or Capturing Motion

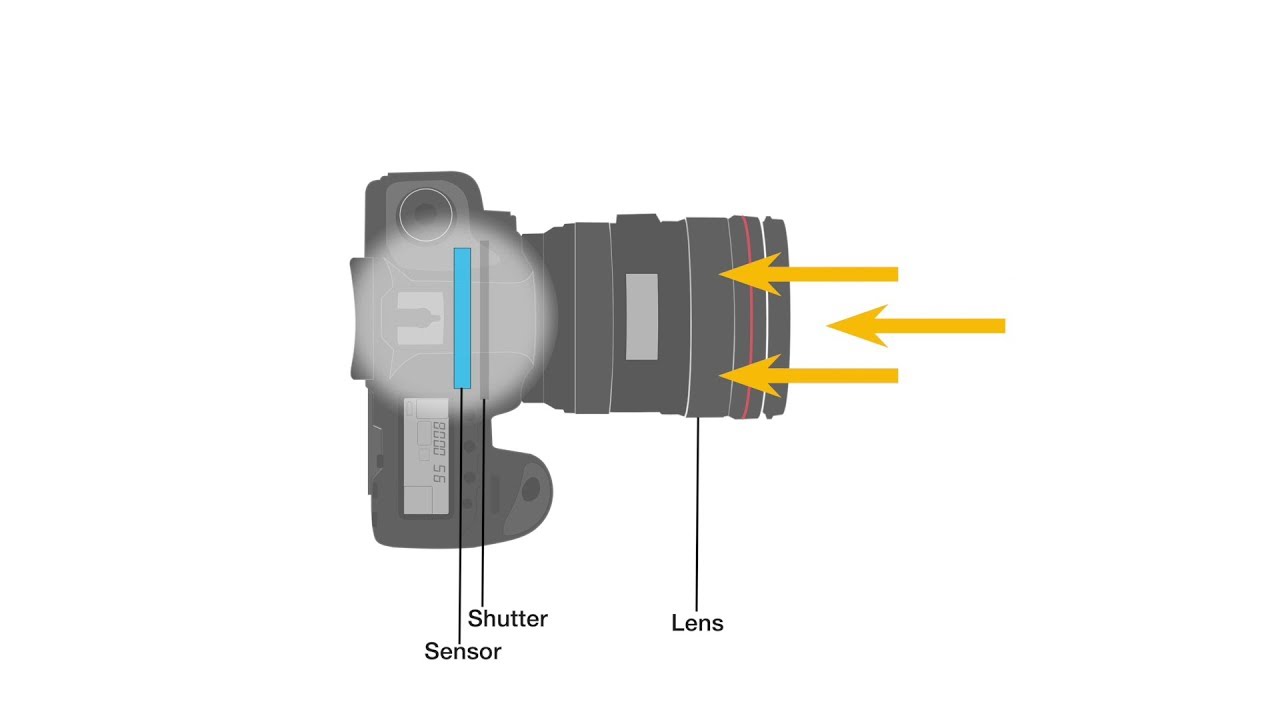

We’ve talked about how cameras control the amount of light entering through the lens, but there’s another crucial factor in capturing an image: time. This is where shutter speed comes into play.

Think of the camera’s shutter as a curtain that quickly opens and closes, allowing light to reach the camera’s sensor for a specific duration. This duration is what we call shutter speed.

To understand shutter speed, let’s imagine you’re at a racing track:

- Fast shutter speed (e.g., 1/1000th of a second): This is like blinking your eyes very quickly. It freezes motion, allowing you to capture a crystal-clear image of a race car zooming by.

- Slow shutter speed (e.g., 1/30th of a second or slower): This is like keeping your eyes open for a longer time. It can create a blur effect, showing the motion of the car as it speeds around the track.

Shutter speed isn’t just about capturing or blurring motion. It also affects how much light enters the camera. A longer shutter speed allows more light in, which is useful in low-light situations. However, it also increases the risk of camera shake, which can make your photos blurry.

This diagram shows how shutter speed affects the capture of a moving object (represented by the red circle). On the left, a fast shutter speed freezes the motion, resulting in a sharp image of the object. On the right, a slow shutter speed creates a motion blur effect, showing the path of the moving object.

Chapter 5: The Digital Revolution – From Film to Sensors

So far, we’ve talked about how cameras control and focus light. But how does this light actually become the image we see? In the past, cameras used light-sensitive film to capture images. When light hit the film, it caused a chemical reaction that recorded the image. However, most modern cameras have gone digital.

Instead of film, digital cameras use a sensor. Think of this sensor as a grid made up of millions of tiny light-catching buckets called pixels. When light hits these pixels, they generate an electrical signal. The strength of this signal depends on how much light each pixel receives.

To help you visualize this, imagine you’re standing in a stadium with thousands of people. Each person has a colored card, and when instructed, they hold up their card to create a giant picture. In this analogy, each person represents a pixel on the camera’s sensor, and the color of their card represents the light information captured by that pixel.

The camera’s processor takes all this information from millions of pixels and combines it to create the final image. It’s like a super-fast painter, mixing just the right colors in just the right places to recreate the scene you photographed.

This diagram illustrates the process of how a digital camera sensor works:

- Light passes through the lens and is focused onto the sensor.

- The sensor is made up of a grid of pixels, each capturing different intensities of light.

- The information from these pixels is then processed to create the final digital image.

Also check: The Magic of Search Engines

Chapter 6: ISO – The Sensor’s Sensitivity to Light

Now that we understand how the sensor captures light, let’s talk about another important camera setting: ISO. ISO determines how sensitive your camera’s sensor is to light.

Think of ISO like this: Imagine you’re trying to catch raindrops in a bucket. A low ISO is like using a bucket with a small opening – it won’t catch many raindrops (light), but the ones it does catch will be very precise. A high ISO is like using a bucket with a wide opening – it’ll catch more raindrops, but some might splash out or you might catch other things too.

In camera terms:

- Low ISO (e.g., 100 or 200): This is great for bright, sunny days. Your images will be clear and crisp, with little digital “noise” (like static on an old TV).

- High ISO (e.g., 1600 or 3200): This is useful in low light situations, like indoor events or night photography. It allows you to use faster shutter speeds or smaller apertures in dim light, but your images might have more noise.

The trick is finding the right balance. Modern cameras are getting better at producing clean images at higher ISOs, but there’s always a trade-off between light sensitivity and image quality.

Chapter 7: Putting It All Together – The Exposure Triangle

We’ve covered a lot of ground, from lenses and apertures to shutter speeds and ISO. But how do all these elements work together? This is where we introduce the concept of the “Exposure Triangle.”

The Exposure Triangle is like a delicate balancing act between aperture, shutter speed, and ISO. Each of these elements affects the exposure (brightness) of your image, and changing one often means you need to adjust the others to maintain the same exposure.

Let’s use a cooking analogy to understand this:

- Aperture is like the size of your pot. A bigger pot (wider aperture) lets you cook more food (let in more light) at once.

- Shutter speed is like cooking time. The longer you cook (slower shutter speed), the more your food will be done (more light enters).

- ISO is like the heat of your stove. Higher heat (higher ISO) cooks food faster but might burn it (introduce noise to the image).

To get the perfect dish (photo), you need to balance all three:

- If you want a shallow depth of field (wide aperture), you might need a faster shutter speed or lower ISO to avoid overexposure.

- If you’re shooting fast action (fast shutter speed), you might need a wider aperture or higher ISO to get enough light.

- In low light, you might need to use a combination of wide aperture, slow shutter speed, and high ISO.

This diagram illustrates the Exposure Triangle, showing how aperture, shutter speed, and ISO interact to create the final exposure. Each corner of the triangle represents one of these elements, and the center represents the resulting exposure. The arrows indicate the range of each setting and its effect on the amount of light or sensitivity.

Also check: The Future of Artificial Intelligence

Chapter 8: From Capture to Memory – Storing Your Images

Now that we’ve captured our image, what happens next? In the days of film, the process would involve chemical development and printing. But in the digital age, we have a new step: saving the image file.

When you press the shutter button on a digital camera, all the information from the sensor is processed and converted into a digital file. This file contains all the data about your image – the colors, the brightness, the details.

Most cameras offer two main types of file formats:

- JPEG (Joint Photographic Experts Group): This is like a zip file for your photo. It compresses the image data to save space, which is great for sharing or when you need to store lots of photos. However, this compression means some data is lost.

- RAW: Think of this as the digital equivalent of a film negative. It contains all the unprocessed data from your sensor. RAW files are larger and need to be processed before sharing, but they give you much more control when editing your photos later.

Choosing between these formats is like deciding whether to buy a ready-made meal or ingredients to cook from scratch. JPEG is convenient and quick, while RAW offers more flexibility but requires more work.

Chapter 9: Beyond the Basics – Advanced Camera Features

We’ve covered the fundamental principles of how cameras work, but modern cameras come with a host of advanced features that can help you take even better photos. Let’s explore a few of these:

- Autofocus: This is like having a robot assistant that quickly adjusts the lens to keep your subject sharp. Modern autofocus systems can even track moving subjects!

- Image Stabilization: Imagine trying to draw a picture while on a bumpy bus ride. Image stabilization is like having a steady hand that keeps your camera still, even if you’re moving a bit.

- Scene Modes: These are like having a professional photographer giving you advice for specific situations. “Sports mode” might automatically choose a fast shutter speed, while “Portrait mode” might select a wide aperture for a blurred background.

- HDR (High Dynamic Range): This is like having superhuman eyes that can see detail in both very bright and very dark areas at once. The camera takes multiple photos at different exposures and combines them.

- White Balance: Our eyes automatically adjust to different types of light, but cameras need help. White balance ensures that white objects appear white, whether you’re in sunlight, shade, or under artificial lights.

Conclusion: The Art and Science of Photography

We’ve journeyed from the simple principle of the camera obscura to the complex digital marvels we use today. Cameras are incredible devices that combine physics, chemistry, and electronics to freeze moments in time.

But remember, while understanding how a camera works is important, it’s just the beginning. A camera is a tool, and like any tool, its true power lies in the hands of its user. The most important elements in photography are your eyes to see the world in a unique way, and your creativity to capture and share that vision.

So go forth with your newfound knowledge! Experiment with different settings, play with light, and most importantly, keep shooting. Every photo you take is a step on your journey as a photographer. Who knows? The next time you press that shutter button, you might just capture a moment that will be cherished for generations to come.

Reply